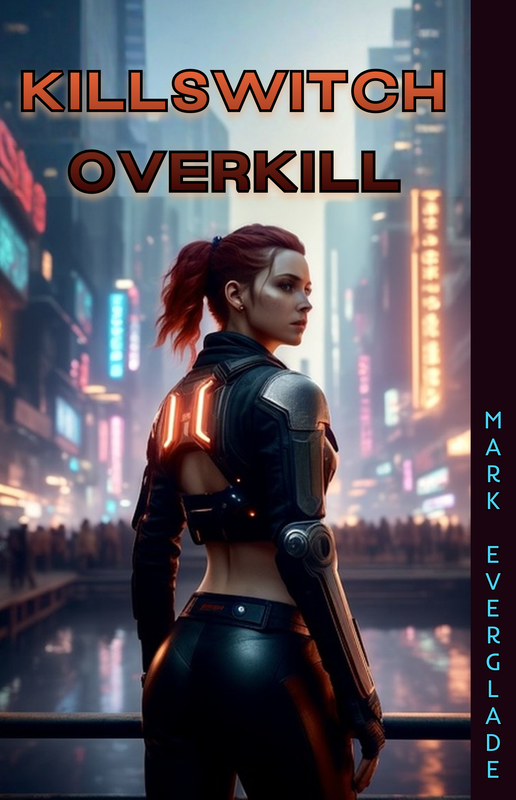

Cyberpunk Series - Book Three

Killswitch Overkill

Killswitch Overkill

|

Chapter 1

The navy sky unfurled across the ocean like a scroll about to reveal the world’s history, but most of the human race wasn’t alive to hear it. Stories of self-sacrifice, heroic feats performed in the name of equality, and celebrations of life were scribed upon the edges of each cloud. But these weren’t my stories, for while others had been risking their lives for a greater cause, I, Sabrina Underfoot, had been weathering the seductions of power, just as the pier I sat upon that day weathered the endless battering of the open sea. I’d seen a lot, but I’d never seen a boy jump off a skyscraper. I nodded to the child standing at the edge of the tower in the floating village of FugaCity, motioning my approval for him to take the leap, for what did it matter at this point? Let the kid take a break from it all. The boy curled his toes around the edge and raised his heels, the wind raking across the ocean below him. He measured the jump, leaned forward, and leapt off the building, the air whisking past as he flayed his small arms until hitting the water seconds later, for most of the skyscraper was submerged beneath the sea. A perfect dive without even a splash. Not bad for a ten-foot jump. The island of FugaCity was anchored at each corner by four skyscrapers, for they were the only buildings tall enough to break the water’s surface. Rusted metal beams stretched between their upper floors, supporting a patchwork of bobbing platforms bound by thick cords. Houses that sat upon floating tires reflected sunlight off the green soda bottles that formed their walls, distorting the images of the people huddled inside them. For over two centuries on this forsaken planet we existed to consume, just as the world consumed us in turn. The broken logo of some long-forgotten entertainment company, Phony, swung back and forth on an old nail, making a clanking sound as metal hit metal. The company with a thousand stores was now worth nothing more than a windchime. The eyes had been shot out of the pink blob that had once been its mascot, the world having lost its sight in the endless quest for new configurations of pixels and plastic, and bowing to any regime that promised them regardless of the cost. |

The sun was a crimson blot against the foggy sky. Lightning shot across with its forked tongue, thunder booming in reply. Winds churned. Rain pummeled tin shacks and lamented over the chrome sea, which rippled in response. The elders motioned for me to get away from the water, but I wasn’t that naïve. Every surface was damp, every moment diluted. If lightning struck, the bolt would surge through the entire village and only Lady Luck would choose the survivors. The lightning rods I installed a half mile from the city offered little hope with the planet’s ever-changing rotational speed, and the storms grew less predictable each week. Everyone knew it was a gamble whether the city would survive another catastrophe, the winds churning us into a mixture of blind hope and helplessness. You couldn’t tell this to children though, and amidst these threats we were all like children.

I dipped my toes into the icy waters once known as the Lost Shores, only there was no shoreline left here with half the world’s cities having sunk during the Great Submersion. The affluent who hadn’t starved or drowned had absconded off-planet, abandoning Gliese 581g as humanity had abandoned Earth centuries before when bioterrorist attacks had rendered it uninhabitable. The pattern played out again and again, destroy one planet and make way for the next.

The child was still underwater following his dive, far too long for such tiny lungs. I shrugged, letting the water pool between my toes. The last few years had been long, the sea of despondency longer yet. The kid was better off with those in the sunken city below anyway, the millions whose bodies still floated like buoys as if marking the end of human arrogance. No, perhaps such haughtiness was the one constant in all this.

It had started with the Great Rotation when terraformer Severum Rivenshear teamed up with an activist group, O.A.K., to increase the rotation of our once tidal-locked planet. Such planets were always dark on one side and light on the other. He thought he would bring daylight cycles to a world that had never known them, thinking it would bring equality. Well, it worked and he toppled the economy and the Old Guard that ruled the Western Hemisphere, but political conflict ensued when the old regime wouldn’t recognize the New Order that took over. The former oligarchs swayed me to get others to spin the planet out of control and wreak havoc on the ecosystem in hopes that people would return them to power to restore stability, so I made the rotational effects worse on purpose. The planet’s rotation soon spun out of control with the sun rising every few hours, and the new heat distribution patterns melted the remaining icecaps, including the ice on the tallest mountains that had not been displacing any water, causing the Great Submersion. Now, everyone was still spinning aimlessly, carrying the legacy of my poor judgment, ‘cause yeah, I fucked up big time. I couldn’t make up for all those drowned souls, all those cities of lost voices engulfed by the careless sea, but perhaps saving one life was a start.

I grabbed a life raft off the pier and threw it at where the child had gone under. I activated sub-Merge by rubbing my nose thrice, enabling me to breathe underwater without an air tank. The cobalt-based molecules freckling my nose produced a fleshy glow through the soft membrane. I bent my knees and dove after him, the water a heavy, icy blanket on my shoulders. Swimming with wide breast strokes, I descended into the depths and that frigid void descended into me in turn. The submerged cityscape was blurry but I could still see where my old apartment was. So many lost homes, so many stories prematurely ended. Pressure built in my ears. I dove deeper until a flaying shape like a blurred ink stain appeared. I approached, cradled the boy, and brought him to the surface, shivering. He gasped and wrapped his arms around my neck. I could barely feel them through my numbness.

What was his name, Forest? Most kids didn’t get a name until their third year of life. No use in getting too attached given the mortality rate. This one was a few years older. Yes, Forest, that was it. I doubted he’d ever seen one.

We climbed back up to the pier. I adjusted my sage, seasilk blouse and bit the sangria strands of my long, damp hair. They tasted of salt and death and the decay of the sea. I needed to get warm, but the red dwarf sun wasn’t even strong enough to tan my pale skin despite being under it all day.

The wind hastened. Waves surged with the white noise of radio static and crashed against the city’s walls of broken furniture. They chiseled at that division between nature and civilization. The dilapidated city creaked and craned its highest points as if seeking dryer quarters. Pipes burst, spurting freshwater everywhere, the floating city’s reservoir draining, and with it any hope we’d survive the week. Mechanics ran in circles, yelling orders, wiping their eyes, and holding out their forearms to block the water pressure. Sparks flew from the solar-powered generators, causing the crooked neon merchant signs to flicker. Whole place was about to go meteor and streak across the sky in a bang if the pipes couldn’t be sealed, but I told the engineers not to place them next to the generators to begin with and now it was their problem. I crossed my legs and rocked on the dock, thinking, Finally some entertainment around here.

Forest bounced from one leg to the next to shake the water from his thin frame and brown, cropped hair. He ran off to meet the rest of the construction crew, all under ten, their drooping overalls too large for their famished figures. He bragged about how long he had held his breath, but the other kids ignored him. They jumped across some floating, wooden platforms and drew silicone guns and wrenches from their belts, traveling along the fractured pipework at the base of the city wall to seal the cracks and ensure the freshwater flow remained separate from the urine running into the recycler, which gargled louder as if on its last leg. These little repairs were just postponing the inevitable. The sea was one unified body, but like space, most of it was empty, hollow, waiting to be filled, to swallow, to devour. In the end, nature would reclaim what was hers including this pathetic village.

Forest glanced my way and waved, then continued addressing the damage. When the last leak was sealed, the other boys banged their tools against the pipes to celebrate with rhythmic drumming, but not Forest, who had mostly completed his repairs in silence. He approached a man tending to some knotwork who was paying the kids a dozen screws and two bolts each for their labor, a hefty earning at their ages, but by the time Forest took his place in line the man walked off with apparently no more to give.

Stupid boy. It’ll just spring a new leak tomorrow. He doesn’t get that the world’s just a toy, and that the reward of work is only more work to do.

Forest approached me with wide eyes and said, “See what I did?”

“FugaCity’s going under one way or another,” I shrugged.

“What does the city’s name mean? You’re old enough to remember.”

“I’m twenty-five, but I guess around here that makes me a survivor. The word fugacity refers to the pressure required for things to escape a heterogenous system. Students learned it in chemistry back when we had science classes.”

“You mean when we actually had schools, though I can barely remember going. Not sure what that city word means but it sure sounds silly.”

“Better than atrocity or paucity, though they fit equally well.”

A stream of water rose from the sea like a transparent snake. Red lights glowed in what appeared to be a head masked by the undulating waves. Its eyes blinked and it writhed like an eel before submerging once more with a beeping sound.

“What was that?” Forest asked.

Someone or something’s watching, I thought. “Nothing. New species or something.” Let the boy have his naivety another year.

“Wow! Well, goodbye,” he exclaimed, skipping through the accumulating puddles. His steps were light, debonair, and each one irritated me.

I shuddered and wrapped my arms about my chest, keeping watch on the waves that reached for the sky one moment just to lay dormant within the depths of the unknown the next. The endless oceanic expanse covered The Crystal Palace, Eisbrecher, Blutengel, and the rest of the hemisphere’s sunken cities. There was nowhere to go, no aim in sight. This hemisphere had plenty of resources but no way to harvest them, while the other side of the planet lacked resources but at least had dry land, and there was nothing between this contradiction but towns like FugaCity that floated at the winds’ whims where life was so destitute that most gave up and voluntarily let the slave ships take them elsewhere, even when humans didn’t pilot them.

I untied my wooden raft and stepped upon the bobbing platform, standing in the middle so I wouldn’t teeter off it. The rough sea rocked the craft, throwing me to the wood where splinters pierced my backside through the gaps in my fishnet pants. I needed to find material for better clothing, but I had to steal the net off a boat just to craft these. Water sloshed upon the deck, raising my light leg hairs with a chilly tingle.

Godrays pierced the dark clouds to shine between the raft’s rotting wooden panels. The raft was barely seaworthy but it was reinforced with a crosshatching of glimmering phosphophyllite crystals. My Eddie used to say the turquoise gems were the same color as my eyes, though he never made contact with them while speaking to me, but that’s another story. The crystals rotated their facets to transmit the light between them, for a variation of the channelrhodopsin protein allowed them to communicate by reacting to light, though the nature of their collective sentience was elusive to us. They were called the Bhasura, and whether they were a phosphorous-based lifeform, or a crystalline manifestation of sentient light, the world knew not, but after going dormant for two years the stones were shining again. They bathed the raft in a soft, jade glow that grew dim when other ships were around as if the lightshow was only meant for me.

Even the stone had trust issues.

Starving, I lowered into the sea, the water filling the shallow hole of my navel with a chill as if I was being born again into the frigid arms of my mother. My shoulders tensed at the thought of her touch, and tensed again at the cold, refusing to accept the lifeless shudder that is the end state of all things. All that global flooding; the millions of dead, and my mother likely among them. I told myself I didn’t care because I was a great liar. I had been orphaned not by her death, but by her indifference towards life. I treaded water with half my vigor, my memories with the other half, and my head barely bobbing above the surface of both.

I dove. The water felt solid, not a fluid body in motion, and I was surprised when it parted to my touch. I rippled my fingers through the water stroke after stroke until resurfacing a few minutes later emptyhanded. Wrinkles gathered in my puffy, waterlogged fingers. I rubbed them together and picked at some sharp metal stuck in my forearms, ready to work off the rumbling in my stomach. Dead fish floated on the sea’s surface, plastic bags extending from their throats, pieces of toy hovercrafts stuck in their gills. Wasn’t worth cleaning a fish like that, so I pushed them and their stink down-current with a wide sweep of my arm. Tendrils of buoyant, slimy seaweed brushed my legs before wrapping around them like tongues. The water was too deep for them to root but this species floated near the surface, hanging its lush greenery below. I swayed with them, gathering them in my arms and diving again to reach a few stragglers. The sounds above gurgled. Scissor-kicking to the surface, I dragged the large bundle of seaweed to my raft and tied it to my makeshift mast, for there was little else to eat with half the world’s arable land underwater and no way to make money. A degree in cybersecurity from Eisbrecher Tech wasn’t that useful when the only technology on the Western Hemisphere that wasn’t hundreds of feet underwater were the myriad implants humming in everyone’s brains with that strange tingling sensation. The only timeless skills were fishing, farming, and politics.

I had fled the floods, weathered the waves, only to return once the waters had risen to Fugacity, since the city floated a few hundred feet above where my apartment was submerged. I needed to do one last sweep of my old home so I could make peace with it being gone; that and I had left a stash of credits in a safe bolted to the floor of my old room, not trusting my funds to insecure cloud servers. I activated a compression protocol in my cognigraf implant and headed deeper than ever.

I dipped my toes into the icy waters once known as the Lost Shores, only there was no shoreline left here with half the world’s cities having sunk during the Great Submersion. The affluent who hadn’t starved or drowned had absconded off-planet, abandoning Gliese 581g as humanity had abandoned Earth centuries before when bioterrorist attacks had rendered it uninhabitable. The pattern played out again and again, destroy one planet and make way for the next.

The child was still underwater following his dive, far too long for such tiny lungs. I shrugged, letting the water pool between my toes. The last few years had been long, the sea of despondency longer yet. The kid was better off with those in the sunken city below anyway, the millions whose bodies still floated like buoys as if marking the end of human arrogance. No, perhaps such haughtiness was the one constant in all this.

It had started with the Great Rotation when terraformer Severum Rivenshear teamed up with an activist group, O.A.K., to increase the rotation of our once tidal-locked planet. Such planets were always dark on one side and light on the other. He thought he would bring daylight cycles to a world that had never known them, thinking it would bring equality. Well, it worked and he toppled the economy and the Old Guard that ruled the Western Hemisphere, but political conflict ensued when the old regime wouldn’t recognize the New Order that took over. The former oligarchs swayed me to get others to spin the planet out of control and wreak havoc on the ecosystem in hopes that people would return them to power to restore stability, so I made the rotational effects worse on purpose. The planet’s rotation soon spun out of control with the sun rising every few hours, and the new heat distribution patterns melted the remaining icecaps, including the ice on the tallest mountains that had not been displacing any water, causing the Great Submersion. Now, everyone was still spinning aimlessly, carrying the legacy of my poor judgment, ‘cause yeah, I fucked up big time. I couldn’t make up for all those drowned souls, all those cities of lost voices engulfed by the careless sea, but perhaps saving one life was a start.

I grabbed a life raft off the pier and threw it at where the child had gone under. I activated sub-Merge by rubbing my nose thrice, enabling me to breathe underwater without an air tank. The cobalt-based molecules freckling my nose produced a fleshy glow through the soft membrane. I bent my knees and dove after him, the water a heavy, icy blanket on my shoulders. Swimming with wide breast strokes, I descended into the depths and that frigid void descended into me in turn. The submerged cityscape was blurry but I could still see where my old apartment was. So many lost homes, so many stories prematurely ended. Pressure built in my ears. I dove deeper until a flaying shape like a blurred ink stain appeared. I approached, cradled the boy, and brought him to the surface, shivering. He gasped and wrapped his arms around my neck. I could barely feel them through my numbness.

What was his name, Forest? Most kids didn’t get a name until their third year of life. No use in getting too attached given the mortality rate. This one was a few years older. Yes, Forest, that was it. I doubted he’d ever seen one.

We climbed back up to the pier. I adjusted my sage, seasilk blouse and bit the sangria strands of my long, damp hair. They tasted of salt and death and the decay of the sea. I needed to get warm, but the red dwarf sun wasn’t even strong enough to tan my pale skin despite being under it all day.

The wind hastened. Waves surged with the white noise of radio static and crashed against the city’s walls of broken furniture. They chiseled at that division between nature and civilization. The dilapidated city creaked and craned its highest points as if seeking dryer quarters. Pipes burst, spurting freshwater everywhere, the floating city’s reservoir draining, and with it any hope we’d survive the week. Mechanics ran in circles, yelling orders, wiping their eyes, and holding out their forearms to block the water pressure. Sparks flew from the solar-powered generators, causing the crooked neon merchant signs to flicker. Whole place was about to go meteor and streak across the sky in a bang if the pipes couldn’t be sealed, but I told the engineers not to place them next to the generators to begin with and now it was their problem. I crossed my legs and rocked on the dock, thinking, Finally some entertainment around here.

Forest bounced from one leg to the next to shake the water from his thin frame and brown, cropped hair. He ran off to meet the rest of the construction crew, all under ten, their drooping overalls too large for their famished figures. He bragged about how long he had held his breath, but the other kids ignored him. They jumped across some floating, wooden platforms and drew silicone guns and wrenches from their belts, traveling along the fractured pipework at the base of the city wall to seal the cracks and ensure the freshwater flow remained separate from the urine running into the recycler, which gargled louder as if on its last leg. These little repairs were just postponing the inevitable. The sea was one unified body, but like space, most of it was empty, hollow, waiting to be filled, to swallow, to devour. In the end, nature would reclaim what was hers including this pathetic village.

Forest glanced my way and waved, then continued addressing the damage. When the last leak was sealed, the other boys banged their tools against the pipes to celebrate with rhythmic drumming, but not Forest, who had mostly completed his repairs in silence. He approached a man tending to some knotwork who was paying the kids a dozen screws and two bolts each for their labor, a hefty earning at their ages, but by the time Forest took his place in line the man walked off with apparently no more to give.

Stupid boy. It’ll just spring a new leak tomorrow. He doesn’t get that the world’s just a toy, and that the reward of work is only more work to do.

Forest approached me with wide eyes and said, “See what I did?”

“FugaCity’s going under one way or another,” I shrugged.

“What does the city’s name mean? You’re old enough to remember.”

“I’m twenty-five, but I guess around here that makes me a survivor. The word fugacity refers to the pressure required for things to escape a heterogenous system. Students learned it in chemistry back when we had science classes.”

“You mean when we actually had schools, though I can barely remember going. Not sure what that city word means but it sure sounds silly.”

“Better than atrocity or paucity, though they fit equally well.”

A stream of water rose from the sea like a transparent snake. Red lights glowed in what appeared to be a head masked by the undulating waves. Its eyes blinked and it writhed like an eel before submerging once more with a beeping sound.

“What was that?” Forest asked.

Someone or something’s watching, I thought. “Nothing. New species or something.” Let the boy have his naivety another year.

“Wow! Well, goodbye,” he exclaimed, skipping through the accumulating puddles. His steps were light, debonair, and each one irritated me.

I shuddered and wrapped my arms about my chest, keeping watch on the waves that reached for the sky one moment just to lay dormant within the depths of the unknown the next. The endless oceanic expanse covered The Crystal Palace, Eisbrecher, Blutengel, and the rest of the hemisphere’s sunken cities. There was nowhere to go, no aim in sight. This hemisphere had plenty of resources but no way to harvest them, while the other side of the planet lacked resources but at least had dry land, and there was nothing between this contradiction but towns like FugaCity that floated at the winds’ whims where life was so destitute that most gave up and voluntarily let the slave ships take them elsewhere, even when humans didn’t pilot them.

I untied my wooden raft and stepped upon the bobbing platform, standing in the middle so I wouldn’t teeter off it. The rough sea rocked the craft, throwing me to the wood where splinters pierced my backside through the gaps in my fishnet pants. I needed to find material for better clothing, but I had to steal the net off a boat just to craft these. Water sloshed upon the deck, raising my light leg hairs with a chilly tingle.

Godrays pierced the dark clouds to shine between the raft’s rotting wooden panels. The raft was barely seaworthy but it was reinforced with a crosshatching of glimmering phosphophyllite crystals. My Eddie used to say the turquoise gems were the same color as my eyes, though he never made contact with them while speaking to me, but that’s another story. The crystals rotated their facets to transmit the light between them, for a variation of the channelrhodopsin protein allowed them to communicate by reacting to light, though the nature of their collective sentience was elusive to us. They were called the Bhasura, and whether they were a phosphorous-based lifeform, or a crystalline manifestation of sentient light, the world knew not, but after going dormant for two years the stones were shining again. They bathed the raft in a soft, jade glow that grew dim when other ships were around as if the lightshow was only meant for me.

Even the stone had trust issues.

Starving, I lowered into the sea, the water filling the shallow hole of my navel with a chill as if I was being born again into the frigid arms of my mother. My shoulders tensed at the thought of her touch, and tensed again at the cold, refusing to accept the lifeless shudder that is the end state of all things. All that global flooding; the millions of dead, and my mother likely among them. I told myself I didn’t care because I was a great liar. I had been orphaned not by her death, but by her indifference towards life. I treaded water with half my vigor, my memories with the other half, and my head barely bobbing above the surface of both.

I dove. The water felt solid, not a fluid body in motion, and I was surprised when it parted to my touch. I rippled my fingers through the water stroke after stroke until resurfacing a few minutes later emptyhanded. Wrinkles gathered in my puffy, waterlogged fingers. I rubbed them together and picked at some sharp metal stuck in my forearms, ready to work off the rumbling in my stomach. Dead fish floated on the sea’s surface, plastic bags extending from their throats, pieces of toy hovercrafts stuck in their gills. Wasn’t worth cleaning a fish like that, so I pushed them and their stink down-current with a wide sweep of my arm. Tendrils of buoyant, slimy seaweed brushed my legs before wrapping around them like tongues. The water was too deep for them to root but this species floated near the surface, hanging its lush greenery below. I swayed with them, gathering them in my arms and diving again to reach a few stragglers. The sounds above gurgled. Scissor-kicking to the surface, I dragged the large bundle of seaweed to my raft and tied it to my makeshift mast, for there was little else to eat with half the world’s arable land underwater and no way to make money. A degree in cybersecurity from Eisbrecher Tech wasn’t that useful when the only technology on the Western Hemisphere that wasn’t hundreds of feet underwater were the myriad implants humming in everyone’s brains with that strange tingling sensation. The only timeless skills were fishing, farming, and politics.

I had fled the floods, weathered the waves, only to return once the waters had risen to Fugacity, since the city floated a few hundred feet above where my apartment was submerged. I needed to do one last sweep of my old home so I could make peace with it being gone; that and I had left a stash of credits in a safe bolted to the floor of my old room, not trusting my funds to insecure cloud servers. I activated a compression protocol in my cognigraf implant and headed deeper than ever.